"I am intent upon the essence of things; the mystery that

lieth

beyond; the elements of the tear which much laughter provoketh;

that

which is beneath the seeming; the precious pearl within the shaggy

oyster.

I probe the circle's center; I seek to evolve the

inscrutable." (2.10)

This is the

strangest, weirdest, queerest book I have ever read. What was Melville

thinking? Mardi, and a Voyage Thither, (1849) could also be subtitled as 'The

Book that Cost a Career'. After the success of his first two novels, Melville

astonished and dismayed his readers with this, his third, effort. During the

writing of it, he wrote in a letter to his publisher: Proceeding in my narrative of facts, I began to feel an incurable

distaste for the same, and a longing to plume my pinions for a flight, and felt

irked, cramped, and fettered by plodding along with dull commonplaces, - so

suddenly abandoning the thing altogether, I went to work heart and soul at a

romance. Critical reception was almost uniformly negative, Melville's

readership declined, and his career never really recovered thereafter. It is probably

the least read of Melville's works: it is double the length of either of his

first two novels, and practically unreadable in large parts.

It begins well

enough, as another sea yarn in the vein of Typee

and Omoo. An unnamed narrator

abandons his whaling ship mid-ocean and mid-voyage after learning that the

Captain is intent on extending the voyage indefinitely. He takes with him a

companion, Jarl, and together, they steal a whale boat in the dead of night,

and make for land, a cluster of islands in the middle of the Pacific, a

thousand miles to the west, a voyage fraught with risk. Melville proceeds in

his tried and trusted method. We are given information about the hazards of

ocean sailing in a small boat, the anguish of being becalmed and watching ones

water and food running out, the terrors of a gale, the huge variety of marine

life, the psychological pressures of enforced co-habitation with another person

in a space not much bigger than a large sofa.

The tussle of genres

Mardi may be seen as a tussle between various genres. It begins

as a realist novel, but then looses all semblance of realism, and enters a

purely allegorical space. Melville may have intended to write a romance, but it

is more correct to say that the second two thirds of the novel have more in

common with the Menippea of Swift, Voltaire, and Montesquieu. The first third

of the novel is wonderful. When Melville is curbing his instincts to

philosophise and act the prophet, his writing is unmatchable. His descriptions

of the sea and its effect on character and mood are magnificent. This part of

the novel teems with unforgettable images and incidents. The whaleman and Jarl

encounter a derelict, described in ghostly terms that make your skin crawl. In

the waters of a hostile archipelago they rescue a beautiful and mysterious

albino maiden named Yillah from a canoe of natives, who are taking her to be

sacrificed to one of their gods. And in one of the most memorable and beautiful

descriptions in the whole of Melville, they come across a shoal of sperm whales

spouting in a sea of phosphorescence: The

sea around us spouted in fountains of fire, and vast forms, emitting a glare

from their flanks, and ever and anon, raising their heads above water, shaking

off the sparkles, showed where an immense shoal of Cachalots had risen below to

sport in these phosphorescent billows. (1.37)

The first clue

that things are going awry with the narrative, however, happens in Chapter 48 of

Volume 1: Something Under the Surface,

which begins normally enough as a description of marine life, but which then

enters the minds of the fishes, giving us their thoughts (!): Swim away, merry fins, swim away! Let him

drop that fellow that halts, make a lane, close in and fill up. Let him drown,

if he can not keep pace, no laggards for us. They then break into a song

and dance routine featuring some execrable poetry:

The first clue

that things are going awry with the narrative, however, happens in Chapter 48 of

Volume 1: Something Under the Surface,

which begins normally enough as a description of marine life, but which then

enters the minds of the fishes, giving us their thoughts (!): Swim away, merry fins, swim away! Let him

drop that fellow that halts, make a lane, close in and fill up. Let him drown,

if he can not keep pace, no laggards for us. They then break into a song

and dance routine featuring some execrable poetry:

We fish, we fish, we merrily swim,

We care not for friend nor for foe:

Our fins are stout

Our tails are out

As through the seas we go. (1.48)

And so on, for

three more stanzas. Things get increasingly weirder, until they arrive at a

mysterious, unmapped archipelago, which they later learn is called Mardi. To

create a good impression, the narrator decides to tell the credible natives

that he is a demi-god named Taji come from the sun to roam in Mardi. (This was

a common ploy when whites encountered natives: Captain Cook, and Pizarro both

used the same lie.) They are brought to the King of the island, Media, and

feasted and feted. During the night, the mysterious Yillah disappears.

Distraught, Taji (as the narrator calls himself from here on) decides to visit

all the lands of Mardi in search of her.

King Media and three

companions decide to accompany Taji on his quest, while Jarl decides to stay

behind, whereupon he is promptly discarded by the narrative, as the last

representative of realism in the text. The three companions are the chronicler

Mohi (aka Braid-Beard), the philosopher Babbalanja, and the poet Yoomy. These

four men, together with Taji, and their retainers and crewmen, set out on three

canoes to visit the other islands in the archipelago. During their travels they

discourse, discuss, bicker, spat and hold forth on a range of topics. Here is a

list of some of them:

the relative

merits of poetry, philosophy and history as a means of knowledge

fame and

reputation

death and the

afterlife

categorising and

naming

faith and

knowledge

psychology and

the nature of the self

religion

bodily aging

the soul

the purpose of

art

art or

entertainment

idolatry

dreams

the nature of

artistic inspiration

recent European

history

the American

scene

the individual's

place in society

the pleasures of

smoking

the nature of

consciousness

the law

laughter

the folly of war

Melville attacks

various sacred cows with what we can call satirical allegory. Let's look at two

of his targets in more detail: religion and the law. Melville's method is to

use episodes on the quest, and discourses among the party, for his satirical

ends.

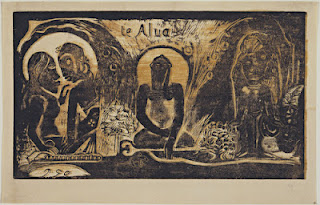

Religion

In Chapter 5 of Volume

2, the travellers arrive at Morai, the burial place of the Pontiffs. They

encounter a group of pilgrims, each one of whom expresses and embodies an

attitude towards religion. A sad-eyed maiden falls to her knees murmuring: "Receive my adoration, of thee I know

nothing but what the guide has spoken... These things are above me... I am

afraid to think." (2.5) embodying the blind faith argument. A rich

matron showers the guide with gifts, embodying the argument that religion is a

social function, and implying a criticism of the wealth of organised religion.

A wilful young man who refuses the ministrations of the guide says: "I may perish in truth, but it shall be

on the path revealed to me in my dream" (2.5), embodying the personal mystical experience of religion. The

guide, who is blind and led by a child, stimulated by the wilful young man's

fervid visions, then launches into a long meditation on his blindness, which

becomes an allegory: "Blindness

seems a consciousness of death." He is riven by doubt: "The undoubting doubter believes the

most." (2.5)

Later they

arrive at a place where idols are manufactured out of tremendous logs.

Babbalnaj asks the idol maker whether he believes in his idols, and receives

this response: "When

I cut down the trees for my idols," said he, "They are nothing

but

logs; when upon those logs, I chalk out the figures of my images,

they yet

remain logs; when the chisel is applied, logs they are still;

and when all

complete, I at last stand them up in my studio, even then

they are logs.

Nevertheless, when I handle the pay, they are as prime

gods, as ever were

turned out in Maramma." (2.10) (The idol

maker has a nice side line in canoes, in which he has cornered the market.)

Later, in a discourse on what they have

seen, Babbalanja, who is usually the chief vehicle for Melville's satire,

offers an anecdote which satirizes the stupidities of theology. Nine blind men

undertake to find the main trunk of a huge Banyan tree. Each one feels among

the roots and tendrils, exclaiming: "Here

it is! Here it is!" They begin to fight, and in doing so change places

around the tree, each one still claiming that he and he alone has found the

main trunk.

The Law

The chronicler Mohi tells the party of

an island in the archipelago called Minda, which is plagued by sorcerers. If a Mindarian

deemed himself aggrieved or

insulted by a countryman, he forthwith

repaired to one of these sorcerers; who,

for an adequate

consideration, set to work with his spells, keeping himself in

the

dark, and directing them against the obnoxious individual. (2.40) The

obnoxious individual then hires his own sorcerer to cast his own spells, until

things get out of hand, and some effort is made to curb the sorcerers. But

fruitless the attempt; it was soon

discovered that already their

spells were so spread abroad, and they themselves

so mixed up with the

everyday affairs of the isle, that it was better to let

their vocation

alone, than, by endeavoring to suppress it, breed additional

troubles. (2.40)

No one understands the spells the

sorcerers use, and they deliberately obfuscate their clients: when interrogated concerning their science, would confound the

inquirer

by answers couched in an extraordinary jargon, employing

words almost as long

as anacondas. (2.40) The sorcerers never attack each other: If from any cause, two sorcerers fell out, they

seldom exercised their

spells upon each other; ascribable to this,

perhaps,--that both being versed in

the art, neither could hope to get

the advantage. (2.40) The satire is

mixed with wisdom: On all hands it was

agreed, that they derived their

greatest virtue from the fumes of certain

compounds, whose

ingredients--horrible to tell--were mostly obtained from the

human

heart (2.40), and it's this

mixture of satire and wisdom which is one of the key characteristics of the

allegorical part of the novel.

Melville achieves a strange effect with

his use of language in these allegorical satires, in which one lexical field

(sorcerers on tropical islands) is used to describe another (lawyers in the

Republic), so that the reader is forced to simultaneously maintain two distinct

and yet connected areas of meaning. This technique is most clearly seen in two places

in the novel, first, when Mohi is describing the quarrels between a group of

islands, namely Porpheero, Dominora, Franko, Vatikanna, Hapzaboro (and more),

which of course are Europe, Great Britain, France, The Vatican and the Habsburg

empire respectively. Mohi then goes on to give a run down of the contemporary

European scene in terms of war between these islands. The satire is wicked:

here is the description of the king of Franko: a

small-framed, poodle-haired, fine, fiery gallant; finical in

his

tatooing; much given to the dance and glory (2.41) and the Pope: --the

priest-king of Vatikanna; his chest marked over with

antique

tatooings; his crown, a cowl; his rusted scepter swaying over

falling

towers, and crumbling mounds; full of the superstitious past;

askance,

eyeing the suspicious time to come. (2.41)

This

technique is most brilliantly done in the section where Babbalanja is

describing the current scientific theories of the origins of the universe, in

terms of food: My

lord, then take another theory--which you will--the celebrated

sandwich System.

Nature's first condition was a soup, wherein the

agglomerating solids formed

granitic dumplings, which, wearing down,

deposited the primal stratum made up

of series, sandwiching strange

shapes of mollusks, and zoophytes; then snails,

and periwinkles:--

marmalade to sip, and nuts to crack, ere the substantials

came.

"And next, my lord, we have the fine old time of the Old Red

Sandstone

sandwich, clapped on the underlying layer, and among other

dainties,

imbedding the first course of fish,--all quite in

rule,--sturgeon-

forms, cephalaspis, glyptolepis, pterichthys; and other finny

things,

of flavor rare, but hard to mouth for bones. Served up with these,

were

sundry greens,--lichens, mosses, ferns, and fungi.

"Now

comes the New Red Sandstone sandwich: marly and magnesious,

spread over with

old patriarchs of crocodiles and alligators,--hard

carving these,--and

prodigious lizards, spine-skewered, tails tied in

bows, and swimming in saffron

saucers." (2.28)

This blending of lexical fields

prefigures the discourse collage of David Foster Wallace.

Parodies

There are

innumerable parodies scattered throughout the book. Babbalanja, the old philosopher

is the chief vehicle for these. Here are two that I recognised, but I daresay

there are many more. Here is Babbalanja parodying Locke in dialogue with Media

and Mohi:

"To begin then, my child:--all

Dicibles reside in the mind."

"But what are Dicibles?" said

Media.

"Meanest thou, Perfect or Imperfect

Dicibles?"

"Any kind you please;--

but what

are they?"

"Perfect Dicibles are of various

sorts: Interrogative; Percontative;

Adjurative; Optative; Imprecative;

Execrative; Substitutive;

Compellative; Hypothetical; and lastly,

Dubious."

"Dubious enough! Azzageddi! forever,

hereafter, hold thy peace."

"Ah, my children! I must go back to

my Axioms."

"And what are they?" said old

Mohi.

"Of various sorts; which, again,

are diverse. Thus: my contrary axioms

are Disjunctive, and Subdisjunctive; and

so, with the rest. So, too,

in degree, with my Syllogisms."

"And what of them?"

"Did I not just hint what they

were, my child? I repeat, they are of

various sorts: Connex, and Conjunct, for

example."

"And what of them?" persisted

Mohi; while Babbalanja, arms folded,

stood serious and mute; a sneer on his

lip.

"As with other branches of my

dialectics: so, too, in their way, with

my Syllogisms. Thus: when I say,--If it

be warm, it is not cold:--

that's a simple Sumption. If I add, But it is

warm:--that's an

_Ass_umption." (2.47)

And here is a parody of Buddhism: However,

my lord, these gods

to whom he alludes, merely belong to the

semi-intelligibles, the

divided unities in unity, this side of the First

Adyta." (2.6)

oooOOOooo

One of the problems with Mardi is that it is extremely hermetic. The range of references, both overt and

covert, is enormous; and unless one is familiar with them, much of the book

goes over the reader's head. You get the feeling that in this novel, Melville

simply abandoned the reader (like Jarl) and wrote the book he wanted to write,

for himself, stretching his art to the limit, both in terms of his linguistic

resources, and in terms of what he wanted to say about his reading and his

thinking. Reading it then becomes almost a pure exercise in the hermeneutics of

Melville's private obsessions and interests - a Herman-eutics, as it were. This

is complicated by the presence of many layers: the narrative voice consists of

Taji telling us what Babbalanja said his hero the poet Bardannia said, and

sometimes Babbalanja is possessed by a devil called Azzageddi, who holds forth.

Even the narrator is not fixed, as he is referred to sometimes as 'Taji' (a

provisional, temporary name for an unnamed narrator) and sometimes as 'I'.

Throughout, however, and this is one of

the chief pleasures of a novel which is not really successful, the language is

glorious. The text is studded with profound and witty epigrams and aphorisms,

and constantly displays a kind of playfulness which catches the reader always

by surprise:

Wherein he resembled my Right Reverend

friend Bishop Berkely - truly, one of your lords spiritual - who,

metaphysically speaking, holding all objects to be mere optical delusion, was,

notwithstanding, extremely matter-of-fact in all matters touching matter

itself. Besides being pervious to the point of pins and possessing a palate

capable of appreciating plum puddings: - which sentence reads off like a

pattering of hailstones. (1.22)

It veers between biting parody, sarcastic

asides, which are the common reaction of the members of the party to

Babbalanja's discourses, song and dance routines of really quite awful poetry

(Melville was absolutely no poet, but he made up for this deficiency by being

one of the very greatest prose stylists in the language), miraculously beautiful

descriptions of nature, especially of sunrise at sea, and wild prophetic

utterances which could have come from a Symbolist text, or from the pen of his

great contemporary Whitman:

And like a frigate, I am full with a thousand souls; and as on, on,

on,

I scud before the wind, many mariners rush up from the orlop

below, like miners

from caves; running shouting across my decks;

opposite braces are pulled; and

this way and that, the great yards

swing round on their axes; and boisterous

speaking-trumpets are heard;

and contending orders, to save the good ship from

the shoals. Shoals,

like nebulous vapors, shoreing the white reef of the Milky

Way,

against which the wrecked worlds are dashed; strewing all the strand,

with

their Himmaleh keels and ribs.

Ay: many, many souls are in me. In my tropical calms, when my ship

lies

tranced on Eternity's main, speaking one at a time, then all with

one voice: an

orchestra of many French bugles and horns, rising, and

falling, and swaying, in

golden calls and responses.

Sometimes, when these Atlantics and Pacifics thus undulate round me,

I

lie stretched out in their midst: a land-locked Mediterranean, knowing

no

ebb, nor flow. Then again, I am dashed in the spray of these sounds:

an eagle

at the world's end, tossed skyward, on the horns of the tempest.

Yet, again, I descend, and list to the concert. (2. 15)

1 comment:

Truly wonderful write up here; love the idea of Herman-eutics. Most of my Melville streams of thoughts right now (including my half-done readings of Mardi and Redburn) are taking a break while I delve into Chinese poetry and its English language permutations, but I am working through "Melville's Quarrel with God" and will have some thoughts on it soon.

Post a Comment