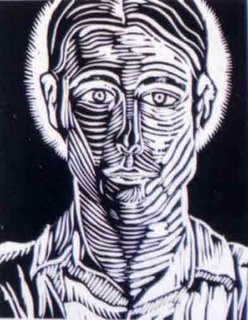

This book has been wrongly positioned by the publisher as a hilarious romp, a work in the line of Vidal’s other romps such as Kalki, Duluth and Myra Breckenridge. However, the bleak cover picture indicates much more accurately the subject, tone and project of the work.

The protagonist is an old man fighting against loss of memory brought about by physical decay and in the process of writing his memoirs. This is a familiar trope for Gore Vidal. Julian (written when the author was 37), Creation (written when the author was 56), Kalki, (written when the author was 53) all feature an old man in a dry month. This stance, surprising in a comparatively young author, allows Vidal to exercise his judgment over his own time with some of the authority of a longer historical perspective, illuminating the follies of his and our age by placing them into a distant past. At the same time it is also perhaps a disguise adopted by an outsider: the marginal position in society of extreme old age masking and mirroring the sexual outsider, the man of above average intelligence, and the holder of unconventional values. (Come to think of it, sexual marginalisation disguised as old age is not an uncommon trope in other ‘gay’ writers too. Consider this opening sentence from Anthony Burgess’s marvelous Earthly Powers, the fictional autobiography of an octogenarian homosexual light-musical composer and popular novelist: It was the afternoon of my 80th birthday and I was in bed with my catamite when Ali announced that the archbishop had come to see me. And then of course there’s Proust, and Yourcenar’s Hadrian.)

This long perspective of history is especially brilliantly done in the opening chapter of the novel, where the technique of defamaliarisation is applied to history itself, and one is not sure whether Vidal is describing an alternative, a kind of what-if scenario, a science fiction scenario light years away into the future, or our own desperate age stripped of all the bullshit. This is not Monty Python at all, but a shamefaced and regretful Tiresias. The voice is very serious, Jamesian in its syntax and disarmingly candid.

I have never found it easy to tell the truth, a temperamental infirmity due not so much to any wish or compulsion to distort reality that I might be reckoned virtuous but, rather, to a conception of the inconsequence of human activity which is ever in conflict with a profound love of those essential powers that result in human action, a paradox certainly, a duel vision which restrains me from easy judgment.

The act of memorization is somewhat crucial. The world has been conquered by a death cult called Cavesword, named after its founder, John Cave (note the initials). The main premise of the cult is that life, consciousness, is an aberration, and that death is the natural state in which we are perfectly at one with the unknowing and uncaring universe. A potion/poison can be administered to adherents called Cavesway, which fills the suicidalist’s dying brain with lively visions and eases the final journey. Governments have succumbed to the cult, and all branches of Christianity have been totally eradicated (if only...). All dissenters are brainwashed and society exists in a kind of ghastly uniformity. Our protagonist, Eugene Luther, it transpires, played a crucial role in the formation of this religion, providing its basic texts and doctrines through his knowledge of philosophy and classical history. When he is recruited to the cause, he has just finished work on the emperor Julian, the last apostate. Writing his memoirs is the final doomed assertion of the truth, which no one will read, except, of course, the reader of the novel.

It is perhaps in this novel more than any of his others that Vidal’s voice aligns itself most closely to his protagonist’s. Certainly there are the usual Vidalian flashes of mordant wit and the occasional outrage. One of the characters responds thus to the increased number of suicides globally as the new religion takes hold: There are too many people as it is, and most of them aren’t worth the room they take up. Overpopulation is another Vidalian trope, one which is always couched throughout Vidal’s career in such a way that the reader is never sure how much irony is to be inferred. Luther ultimately loses out in a power struggle between the publicist Paul Himmel, who plays Paul of Tarsus to John Caves’s Jesus. Luther's final defeat results in his name being totally expunged from all the official records, and he has become a non-person, hiding out in the Valley of the Kings on the Nile, another gay, death-obsessed location (Echoes of Paul Bowles and Andre Gides’ The Immoralist).

So much for the plot. Much of the intellectual debate is couched in the form of Platonic dialogues between two characters, a form which Luther uses to expound Cave’s nihilistic views in the works he ghost-writes for him.

“There’ll be a time when all people are alike.”

“Which is precisely the ideal society. No mysteries, no romantics, no discussions, no persecution because there’s no one to persecute. When all have received the same conditioning, it will be like…”

“Insects.”

“Who have existed longer than ourselves and will outlast our race by many millennia.”

“Is existence everything?

“There’s nothing else.”

The essential conflict revolves around Luther’s realization that if Cavesword is right, then life must be celebrated, and the others’ insistence that death must be sought. We have art on the side of life, and publicity, media manipulation and marketing techniques on the side of death, resulting ultimately in the death of Western Civilization, as all history prior to the life of Cave is erased and forgotten, and Western culture succumbs to the banality of the media.

The book of course operates as a spoof on all religions, including the myth of Isis and Osiris, as Iris Mortimer reenacts an annual nation-wide pilgrimage gathering Cave’s ashes, which have been scattered over three different states. Psychoanalysis and the new age religions also come under scorching satirical fire. However, it is Christianity that comes in the for the worst savaging. The portrayal of a religion’s struggle for advancement in its early days has resonance that extends all the way back to Paul of Tarsus’s Epistles to the Romans and Corinthians, the great schisms in the first thousand years after Christ, the apostasy of Julian, and the final triumph of the ‘new’ religion in the person of Constantine.

The novel echoes many of the great dystopian novels of the century, Orwell’s 1984 –the world has been divided into three Religious Zones- and Brave New World; many aspects of real history: Stalin’s purges, the establishment of the temporal power of the Papacy; and echoes of many real cults: Scientology, Jim Jones, Anthroposophy and so on.

At the heart of the novel, around whom all the action and doctrine revolves, is the character of John Cave himself, who, in spite of charismatic and hypnotic eyes, is weirdly mediocre. He does not relate to people, has no real ambitions, is distinctly colorless and longs only to be traveling, choosing places to visit from a travel catalogue on the basis of their euphonious names alone: Tallahassee and Syracuse. His ideas and the religion he founds, with its empty, vacuous ritual and disappointingly banal terminology represent the power of mediocrity transcendent over all, by means of the power wielded by unscrupulous media manipulators. In this novel, defenders of the truth, of life and of the values associated with our long tradition have been pushed to the edge, and threaten, through their own decline, to vanish from the scene altogether.

Like all Vidal novels, this one includes an –ix word: in this case ‘victrix’. I think it must be a private joke with Vidal to include this strange and lovely suffix in every novel: Creation, and Empire have ‘executrix’ and Kalki has ‘aviatrix’. As I read through the Vidal canon, it’s a game I play with myself, to spot the ix.

Penguin Classics edition

2 comments:

The characterization of Anthroposophy as a cult seems oddly out of place next to Jim Jones and Scientology, not only because it is comparatively obscure but also has nothing in common at all with these other examples.

Oddly enough (given its relative obscurity) "Messiah" was the first book by Vidal that I ever read, and I have remained a fan of his ever sense. It seems to be one of those rare books that gains relevance as time goes on. I think that, just as Mark Twain has gone down in history as the greatest American writer (perhaps the greatest writer, period) of the 19th century, Vidal will go down as the greatest writer of the 20th century. His reputation will far surpass that of his great nemesis, William F. Buckley, Jr.

In reading Vidal, I have often been struck by the thought: this man is a conservative. His work breathes the glorious conservative sense that life is larger than logic -- not, as the fundamentalists and others would have it, smaller than logic -- but beyond the scope of any prefabricated ideology, however ingeniously contrived. It is an insight that is generally lost in American culture, by both the "left" and the "right". Indeed, I think that many of our problems are traceable to the fact that we have never had a genuine conservatism in this country.

Viewed with an open mind, Vidal's work stands as a necessary and enjoyable corrective to that state of affairs.

Post a Comment